Tune Up: Convolution Reverb

posted in: Features • Reviews & Playlists

One of the most widely used techniques when editing/processing audio is, of course, reverb. This echoing, distance effect is age old with audio engineers. Of course, if you’ve used spring reverb amps or really old mixer console reverbs, you know how unrealistic they can sound sometimes. Occasionally that’s a sound people go for. However, in this article, we’re going to share one of my favorite tricks to audio production when it comes to reverb. We’re talking about convolution reverb.

One of the most widely used techniques when editing/processing audio is, of course, reverb. This echoing, distance effect is age old with audio engineers. Of course, if you’ve used spring reverb amps or really old mixer console reverbs, you know how unrealistic they can sound sometimes. Occasionally that’s a sound people go for. However, in this article, we’re going to share one of my favorite tricks to audio production when it comes to reverb. We’re talking about convolution reverb.

If you’re not certain what convolution is, we’ll get to that in a moment. What we want to do first is entice you with one of the amazing things that can be done using this processing technology. Among other things, you can capture the reverberating characteristics of any room, hall or space, bring that data to your DAW and superimpose it on any recorded audio you have. Thus, you’ve made it sound like a specific audio file was recorded in a completely different space.

We’ll step back for a moment and describe, briefly, what convolution is. This basically refers to taking the characteristics of one audio file and applying them to the frequencies of another. In mathematics, the computer takes discrete digital audio data (basically, sets of amplitudes and frequencies), and multiplies them with those of another audio file. Therefore, you can use convolution for a lot of things, making a lot of really interesting sounds. I’ve done everything from creating the sound of a cat meowing through a symbol to a guitar riff that is played with the attacks of a clarinet being blown. It’s really quite amazing.

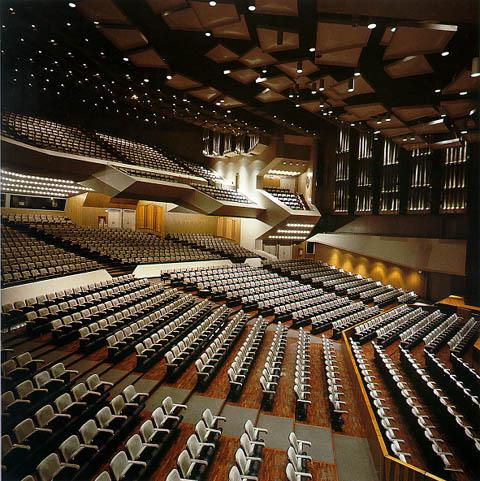

But, for more practical, universal applications, you can create interesting reverb for a track using the same principles. This can be a complicated concept to explain, so we’re going to try and break it down. Convolution takes certain qualities of one audio file and superimposes them onto another audio file. So, in this case, we’re interested in the reverberating qualities of one sound being superimposed onto another (say, a vocal or a guitar track). So, what type of sound really features the echoing qualities of a space? Well, a short, loud and non-pitched sound. This is called an impulse response. All you need to do is set up a few microphones in the space you’re interested in (your local church, a huge auditorium, etc.), and clap. You can also use a snare drum or hit pieces of wood together (some articles say that the closest real-world representation of an impulse response is the shot of a starter pistol, but who owns one of those?). The goal here is to just get a very distinct recording of the space’s reverb. So, make your impulse as short as possible to capture the full reverb tail.

But, for more practical, universal applications, you can create interesting reverb for a track using the same principles. This can be a complicated concept to explain, so we’re going to try and break it down. Convolution takes certain qualities of one audio file and superimposes them onto another audio file. So, in this case, we’re interested in the reverberating qualities of one sound being superimposed onto another (say, a vocal or a guitar track). So, what type of sound really features the echoing qualities of a space? Well, a short, loud and non-pitched sound. This is called an impulse response. All you need to do is set up a few microphones in the space you’re interested in (your local church, a huge auditorium, etc.), and clap. You can also use a snare drum or hit pieces of wood together (some articles say that the closest real-world representation of an impulse response is the shot of a starter pistol, but who owns one of those?). The goal here is to just get a very distinct recording of the space’s reverb. So, make your impulse as short as possible to capture the full reverb tail.

Now that you have the echoing sound you’d like to apply to your mix, you need the right program or plug-in. Many DAW and music software companies offer a convolution reverb system or plug-in. Please note that these can often be called Impulse Reverb processors. Cakewalk makes a great convolution reverb system called Perfect Space. It’s really quite intuitive as to making your own spaces using raw audio. While you can take your hand clap, echoing sound and put it in as a preset for your own convolution spaces, the plug-in also contains a lot of presets that utilize impulse responses recorded at many different cathedrals, auditoriums and spaces worldwide. Therefore, simply assign the plug-in to the audio track.

Like many things on the topic of music technology, this concept is easier heard than explained. Below is a twenty second acoustic guitar clip with no reverb (“dry” as engineers say):

Basically, the real benefit to this is giving your reverb an edge that no one else has. Sure, many reverb engines can try and model large spaces using feedback, wet/dry mix and reverb length, but wouldn’t you rather have the real thing? We’ve found it particularly useful with strings/orchestral sounds. This way, you can take string samples that are dry and easily altered and apply an impulse response from, say, your college’s concert hall. The result is that those string sounds that you got from your DAW sound as if they were recorded in that same concert hall. It’s really quite amazing. So, next time you’re in a really cool space, but can’t feasibly imagine a way to get your amp/guitar in there to record, just record the impulse response on a field recorder and apply it later. You might even be like me and start your own collection of impulse recordings.