Industrial Revolution: Audio Files For Audiophiles

posted in: Features • Music News

Woah. Death came to two digital music pioneers within just a couple of days of each other. Max Matthews, widely considered the father of computerized music, died on April 21st. Two days later, the inventor of the compact disc, Sony’s Norio Ohga, also passed away.

Woah. Death came to two digital music pioneers within just a couple of days of each other. Max Matthews, widely considered the father of computerized music, died on April 21st. Two days later, the inventor of the compact disc, Sony’s Norio Ohga, also passed away.

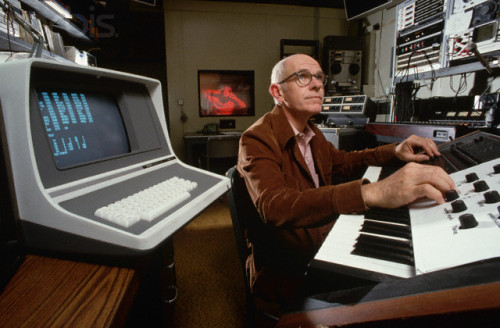

In 1957, Matthews, then working for Bell Labs, wrote a program called Music, which played back synthesized sounds according to the user’s input. His work is the foundation upon which all subsequent computer music, including his own additional innovations, have been built.

Ohga, who led Sony’s immense growth as president from 1982 through 1995, pushed for the development of the media-revolutionizing compact disc. In addition to determining the size of the disc, the classical music lover and former aspiring opera singer famously mandated the CD’s 75-minute running time so that it would fit the entirety of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. Ah, when music fans were in charge¦

Max Matthews

Digital music evolved greatly in the intervening years and beyond. Matthews’ initial forays inspired more the actual creation of synthesizer music, rather than the development of digital formats. It wasn’t until 1975 that Betamax developed high-fidelity digital audio to their compact video cartridges (ultimately falling to the competing VHS format, which quickly caught up to Beta’s audio quality). 1978 similarly saw an audio development married to a video format in the Laserdisc, the first optical disc storage format available commercially, which offered unparalleled audio quality in terms of home video. However, due to the high cost of discs and players alike, along with its inconvenient size (about that of a vinyl LP, but heavier), the Laserdisc never truly caught on.

Norio Ohga

But both of these developments were important steps in the evolution of digital music. The Laserdisc is essentially a giant CD and led directly to the game-changing success of that smaller format, first made available in 1982 by Norio Ogha’s Sony. The CD itself inspired further innovations”the High Definition CD and MiniDisc are obviously direct descendants, and Digital Audio Tape (DAT) owes more to the CD than the compact cassette.

Then around 1988, Apple Inc. introduced the Audio Interchange File Format (AIFF), a non-compressed digital file that could store pieces of audio for personal use. AIFF is still widely used today by audio professionals, along with the Waveform Audio File Format (WAV) and Digidesign’s Sound Designer II (SDII). While there have been additional improvement in tangible formats (DVD, DualDisc, Blu-ray), the real leap forward was in 1993, when the MPEG Audio Layer III (MP3) successfully compressed audio files into a manageable size without rendering the sound quality so low as to be an unfaithful or unlistenable reproduction.

Laserdisc: its the FUTURE!

The MP3, in tandem with Internet technology, has obviously led to file sharing, and the myriad of opportunities and problems that ensued have forever altered the music industry. While no one can dispute the usefulness of the MP3, it is lamentable that it is quickly becoming the standard for audio consumption. You don’t have to be an audiophile to hear the difference between compressed and un-compressed music.

All this begs the question of what’s next for digital audio? Will consumers demand higher quality? Will lossy MP3s be the standard for decades to come? Or will the demand to fit more information in less space extend a tolerance for even a lower-quality format (or lower bit-rate MP3s)? It would be nice if, as professional music recording technology and fidelity standards continue to improve, consumers rightly clamor for an improvement in fidelity, either via format or, more likely, via technology that can handle more lossless files, like WAV and AIFF, in less space. Some people won’t have an interest in improving the sound of their music beyond what MP3s can provide. As their iPod is able to hold more information, they are more likely to see this as an opportunity to fit more MP3s. But some will certainly trade off better quality for at least the same song capacity.

A good sign is Apple’s development of the Apple Lossless format (ALE or ALAC, denoted by the .m4a extension), which is now in use for iTunes, both in converting CDs and for music purchases. This is still proprietary, though, and is not easily shared, especially onto PC and Windows-based computers. Certainly, more innovations are to come, and hopefully ones that support higher quality audio. Hopefully music lovers in the mold of Max Matthews and Norio Ogha are on the case. R.I.P., gentlemen.