Riffs, Rants & Rumors: The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Gary Numan

posted in: Exclusive Interviews • Features • Rock

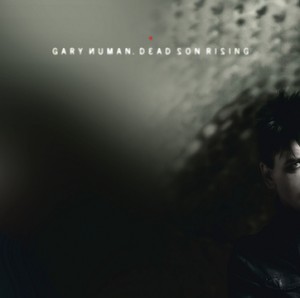

“For me it’s the machine that works best,” says Gary Numan of the synthesizer, the instrument whose use in rock he helped to revolutionize back in the late ’70s. It’s an axe that has certainly served him well over the decades, from the synth-punk experiments of his early recordings to the sleekly designed electronic speedway of his blockbuster breakthrough, “Cars,” all the way up to his latest album, Dead Son Rising.

“For me it’s the machine that works best,” says Gary Numan of the synthesizer, the instrument whose use in rock he helped to revolutionize back in the late ’70s. It’s an axe that has certainly served him well over the decades, from the synth-punk experiments of his early recordings to the sleekly designed electronic speedway of his blockbuster breakthrough, “Cars,” all the way up to his latest album, Dead Son Rising.

But Numan didn’t start out as a synthesizer whiz at all. “Originally I was a guitar player,” he recalls, “and when I was signed to Beggars Banquet we (Tubeway Army) were a guitar, bass and drums three-piece, a punk band, really. I had never played a keyboard before.” As fate would have it, a synth was laying around the studio during the recording of Numan’s first album, and he couldn’t help trying it out. “Soon after that, my parents bought an old upright [piano],” he says. “I started pretty much writing songs on piano from then on. I’ve written two songs on bass guitar in my life,” he adds. “One of those was ‘Cars.'”

But while Numan made new wave history at the end of the ’70s and the onset of the ’80s, his tenure at the top of the heap was fleeting. He confesses that his career “started to suffer somewhat in the early ’80s,” and by the ’90s his star had sputtered out. “I couldn’t give away albums, even in the UK,” he admits. “I couldn’t give away tickets to gigs. I was really, really in trouble, I had massive money problems, all sorts of personal problems at home, it was just a grim time, really…my situation was so poor that I didn’t have a record contract either. I just decided that I was really finished, and I didn’t know if I’d ever make any more albums again. So I went back to what I did before I’d ever done it for a living, and that was to write songs for the fun of it. It went back to being a hobby. And because I wasn’t thinking about career, or trying to please A&R departments, I just went back to writing songs for me, it was immediately different. I hadn’t realized it, but I think for several years before that, everything I’d been writing was desperate attempts to save the career and to try and get back on radio¦listening to advice and trying to keep people happy. That’s when I sold out, I think.”

But while Numan made new wave history at the end of the ’70s and the onset of the ’80s, his tenure at the top of the heap was fleeting. He confesses that his career “started to suffer somewhat in the early ’80s,” and by the ’90s his star had sputtered out. “I couldn’t give away albums, even in the UK,” he admits. “I couldn’t give away tickets to gigs. I was really, really in trouble, I had massive money problems, all sorts of personal problems at home, it was just a grim time, really…my situation was so poor that I didn’t have a record contract either. I just decided that I was really finished, and I didn’t know if I’d ever make any more albums again. So I went back to what I did before I’d ever done it for a living, and that was to write songs for the fun of it. It went back to being a hobby. And because I wasn’t thinking about career, or trying to please A&R departments, I just went back to writing songs for me, it was immediately different. I hadn’t realized it, but I think for several years before that, everything I’d been writing was desperate attempts to save the career and to try and get back on radio¦listening to advice and trying to keep people happy. That’s when I sold out, I think.”

But getting back in touch with his own artistic inspiration soon turned things around for Numan. “I did an album called Sacrifice in ’94, and that was quite a departure for me,” he explains. “The album before that had been called Machine and Soul, and that was by far the worst album I ever made. My songwriting was shit, for one thing.” Sacrifice rekindled Numan’s musical passion in a very visceral way, he says. “It was as if I rediscovered all the love and enthusiasm for it I used to have when I was a teenager, that had slowly been eroded and sucked away by this desire to get back to the successful status that I’d had before.”

The change in direction brought a new wave of audience interest with it. “It was a much heavier, darker record,” Numan says, “and I was really proud of it. Then, surprisingly to me, it actually started to do much better. People started coming to the shows again. It was completely unexpected but unbelievably welcome. And I learned a massively important lesson from that. If I even begin to think, ˜Oh, that might be a hit single,’ I erase the fucking thing. I don’t want to get back into that way of thinking. It’s just soul-destroying and horrible. Don’t listen to anybody, just do what you want to do, and if you do have some success, it’s important that you have it on your own terms, not because you followed some clever A&R man’s advice about doing cover versions, all that horrible stuff that you can get lost in.”

The change in direction brought a new wave of audience interest with it. “It was a much heavier, darker record,” Numan says, “and I was really proud of it. Then, surprisingly to me, it actually started to do much better. People started coming to the shows again. It was completely unexpected but unbelievably welcome. And I learned a massively important lesson from that. If I even begin to think, ˜Oh, that might be a hit single,’ I erase the fucking thing. I don’t want to get back into that way of thinking. It’s just soul-destroying and horrible. Don’t listen to anybody, just do what you want to do, and if you do have some success, it’s important that you have it on your own terms, not because you followed some clever A&R man’s advice about doing cover versions, all that horrible stuff that you can get lost in.”

Both the stylistic shift and the DIY, follow-your-bliss approach to record production have remained near the top of Numan’s artistic agenda ever since, and his new album, Dead Son Rising, follows suit. Keeping with the moves he’s been making over the course of his last few albums, the guitars”yes, guitars”have a harder edge, and there’s a distinct dash of industrial rock on a number of the record’s tracks. Numan still loves his synths, of course, but he’s no fetishist for the classic analog gear he started out with. “On this one it’s all digital. I don’t really care where these things come from. At the moment I’m using a huge amount of software synths. There’s absolutely unbelievable pieces of software out there now that just give people like me no end of inspiration, and sources to create sounds. I like to make sounds, and I’m supplied with tools that make that job incredibly easy.”

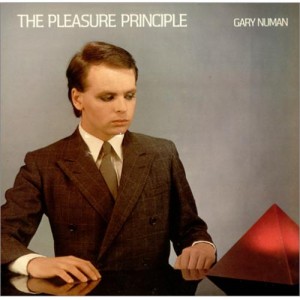

Similarly, while milestone Numan releases like Replicas and The Pleasure Principle boast a flesh-and-blood drummer, he’s not wedded to the concept of a human rhythm section these days either. “I’m not really a purist about it,” he says, “when it comes to playing live, I don’t think you can beat having a drummer up on the stage with you. In the studio I’m less purist about it, and if I do come across a particularly good loop or sample, I’m just as likely to use that as I am to get a real drummer, providing the groove is strong and powerful.” Strong powerful grooves aren’t exactly in short supply on Dead Son Rising, and according to Numan, that’s a trend we can expect him to continue. “The new album that I’m working on now, to follow up the Dead Son Rising album, is just huge in sound,” he enthuses.

Similarly, while milestone Numan releases like Replicas and The Pleasure Principle boast a flesh-and-blood drummer, he’s not wedded to the concept of a human rhythm section these days either. “I’m not really a purist about it,” he says, “when it comes to playing live, I don’t think you can beat having a drummer up on the stage with you. In the studio I’m less purist about it, and if I do come across a particularly good loop or sample, I’m just as likely to use that as I am to get a real drummer, providing the groove is strong and powerful.” Strong powerful grooves aren’t exactly in short supply on Dead Son Rising, and according to Numan, that’s a trend we can expect him to continue. “The new album that I’m working on now, to follow up the Dead Son Rising album, is just huge in sound,” he enthuses.

Having been through the mill of rock stardom, Numan, now fifty-three, is authentically humble about the name he’s made for himself. Musing on the continued popularity and influence of 1979’s The Pleasure Principle, he says, “There was a lot of people discovering electronic music at that time, and I think for some people, the Pleasure Principle album was the one they turned to first, or most.” But Numan reveals that his own goal at the time was to achieve something on the level of his own idols, Ultravox, whose lead synth player”Billy Currie, he uncoincidentally hired to play with him. To this day, the self-effacing Numan feels he never reached that personal goal, despite his renown. “I have all this credibility and people talk about me as being influential,” he says, “which I’m genuinely grateful for. It’s a lovely thing and I’m proud of it, but I still have the other reference, of me never achieving what I wanted to achieve.” Of course, it’s that very lack of self-satisfaction that bodes best for Numan’s continuing relevance as an artist.