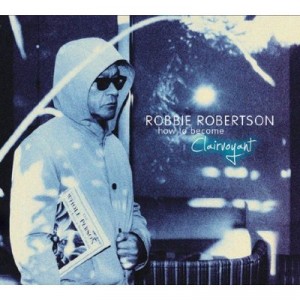

Riffs, Rants & Rumors: Robbie Robertson's Rootsy, Rockin' Return

posted in: Features • Music News • Rock

Those whose hearts palpitate in time to the songs of Robbie Robertson”both his Band-era milestones and solo hits such as Broken Arrow and Somewhere Down The Crazy River” have had to endure a long period of silence from the legendary singer/songwriter/guitarist. Robertson’s last album was Contact From the Underworld of Redboy, a 1998 release informed by the electronic sensibilities of producer Howie B. But just a couple of weeks ago, the thirteen-year silence was broken by He Don’t Live Here No More, the first single from Robertson’s fifth solo album, How To Become Clairvoyant, which is scheduled for an April 5 release. The single, like much of the album itself, bears a deep, swampy, blues-rock groove and a natural-sounding, lived-in feel that has more in common with Robertson’s early solo outings than his last couple of releases, which boasted a more modernized approach. The production style proves to be the perfect complement to the tunes, which share a retrospective, even nostalgic purview. I can’t think of one song on the record that doesn’t have that quality, affirms Robertson, during our conversation about Clairvoyant.

Those whose hearts palpitate in time to the songs of Robbie Robertson”both his Band-era milestones and solo hits such as Broken Arrow and Somewhere Down The Crazy River” have had to endure a long period of silence from the legendary singer/songwriter/guitarist. Robertson’s last album was Contact From the Underworld of Redboy, a 1998 release informed by the electronic sensibilities of producer Howie B. But just a couple of weeks ago, the thirteen-year silence was broken by He Don’t Live Here No More, the first single from Robertson’s fifth solo album, How To Become Clairvoyant, which is scheduled for an April 5 release. The single, like much of the album itself, bears a deep, swampy, blues-rock groove and a natural-sounding, lived-in feel that has more in common with Robertson’s early solo outings than his last couple of releases, which boasted a more modernized approach. The production style proves to be the perfect complement to the tunes, which share a retrospective, even nostalgic purview. I can’t think of one song on the record that doesn’t have that quality, affirms Robertson, during our conversation about Clairvoyant.

Robertson’s got some old friends helping out on the record too, including Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood. Eric and I first started talking about doing something like 10 years ago or more, Robertson recalls, and we got together, but we didn’t have anything specific in mind. We’re old friends, so we were hanging out and playing a little music and telling stories¦but it was just kind of dipping our toe in the water. Him and I did a few things probably over a three-week period when he was in Los Angeles. Some time later¦I came across the project that him and I had started, and I thought ˜Wow, there’s much more here than what I remembered.’ So I called him and I said ˜We’ve got some interesting stuff that we started,’ and he said ˜I always thought so.’ The next thing he knew, Robertson was on a plane to London at Clapton’s behest, to record a full-blown album. He was just a great friend in all of it, Robertson says of the British guitar hero, just being so supportive. He said ˜I just want you to make a record. If I can be part of it and be supportive in it, I’m just glad to do it.’ So that was nice inspiration too. Another old compatriot on hand for the sessions was Steve Winwood. I met Steve when I was 20-years-old and I was playing with Bob Dylan, and we were touring England, recalls Robertson. That was in 1966 I think, so I’ve known him that long.

But Robertson’s other musical endeavors elongated the production process of Clairvoyant. The London tracks turned out well, but Right after we cut them, Martin Scorsese asked me if I would help him figure out the music for Shutter Island, says Robertson. So I went off and did that. It was a more lengthy process than I thought, because for that soundtrack I wanted to use modern classical music, and although I knew something about what that was, I wanted to do more research. So the work on that¦it took a while. Then I came back to the record, and I finished it up by myself and with the other people that I brought in to work on it, like Trent Reznor and [ex-Rage Against The Machine guitarist] Tom Morello and Robert Randolph. So how did industrial-music icon Trent Nine Inch Nails Reznor end up in the mix? In this last little while, he’s been leaning in a cinematic direction, explains Robertson, and he did the music for Social Network. This song that Eric and I had written, Madame X, we had laid down a basic track, but what I was really looking for was¦something that had a timeless quality to it, but I wanted to put a new, modern kind of spin on it as well. I thought those two worlds would fit together really nice, so I asked Trent if he would do a treatment on this.

But despite the occasional presence of more contemporary-minded contributors like Reznor and Morello, How To Become Clairvoyant remains a rootsy, earthy piece of work, and the songs seem to touch on earlier phases of Robertson’s life. This Is Where I Get Off, for instance, deals with his split from his buddies in The Band, while Straight Down The Line celebrates pre-rock & roll-era artists’ insistence on standing their stylistic ground, regardless of changing trends. Robertson says the seed of the idea had to do with Mahalia Jackson. I had suggested a few years ago that she be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an early influence, he says, because she was a complete inspiration, and she’s one of the greatest female singers of all time. And the answer back from her family was ˜That’s okay, we’d rather not.’ Because she always said ˜I do not play no rock and roll.’ [a key line in Robertson’s song] And Frank Sinatra, when rock and roll first came out, he was like, ˜Well this shit’s only gonna be around for six months anyway.’ I just like that attitude, some people were just bold enough to say ˜Nah, I don’t buy it.’

When The Night Was Young looks back wistfully on the idealism of the ˜60s counterculture that 67-year-old Robertson was part of. The youth of the nation, and the youth of the world, ultimately felt like ˜We’re not just gonna stand here and watch wrong things happen, we’re gonna stand up and we’re gonna make a difference.’ That war [in Vietnam] was called to a halt, because everybody said ˜We don’t want this,’ and it really was the voice of a generation telling the governments and the world ˜You’re gonna have to stop this.’ And they did. When we played at Woodstock, people were getting up saying ˜There’s a half a million of us here, and we’re all here today for peace, and we want this war to go away.’ And at that point people were saying ˜You know what, we’re gonna have to listen to some of this shit, we just can’t ignore it anymore.’ It was a powerful feeling, and we don’t have that now, we don’t really feel that in the air.

When The Night Was Young looks back wistfully on the idealism of the ˜60s counterculture that 67-year-old Robertson was part of. The youth of the nation, and the youth of the world, ultimately felt like ˜We’re not just gonna stand here and watch wrong things happen, we’re gonna stand up and we’re gonna make a difference.’ That war [in Vietnam] was called to a halt, because everybody said ˜We don’t want this,’ and it really was the voice of a generation telling the governments and the world ˜You’re gonna have to stop this.’ And they did. When we played at Woodstock, people were getting up saying ˜There’s a half a million of us here, and we’re all here today for peace, and we want this war to go away.’ And at that point people were saying ˜You know what, we’re gonna have to listen to some of this shit, we just can’t ignore it anymore.’ It was a powerful feeling, and we don’t have that now, we don’t really feel that in the air.

On How To Become Clairvoyant, the listeners who grew up with Robertson’s music will recognize pieces of their own past, but younger generations can still get a feeling for the sense of history that pervades the album. The tunes themselves, of course, come with no age requirements for their enjoyment, and Robertson’s followers can exhale at last, content in the knowledge that their pied piper is back at work. I choose to make records when I feel inspired to do so, he says, otherwise I’d rather not, and inspiration appears to have been a key ingredient in Robertson’s latest sonic statement.