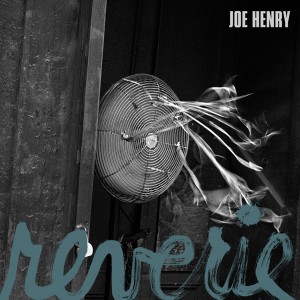

Riffs, Rants & Rumors: Joe Henry's Rumbling, Rattling 'Reverie'

posted in: Features • Rock

Joe Henry has been exploring the relationship between songs and their aural atmosphere for a quarter of a century. His early albums cloaked his carefully crafted compositions in a variety of artful atmospheres provided by other producers, like T-Bone Burnett and Anton Fier, but he began to hit his stride in the early ˜90s, when he took the production reigns himself on a pair of albums”Short Man’s Room and Kindness of the World”that found him backed by alt-country heroes The Jayhawks. With 1996’s Fuse, Henry began pursuing an increasingly unconventional production muse, employing everything from ambient synthesizer textures to the saxophone of Ornette Coleman (the jazz giant plays on 2001’s Richard Pryor Addresses a Tearful Nation). With each album from Fuse up through 2009’s Blood From Stars, Henry’s production became increasingly more impressionistic, but his latest, Reverie, marks a reversal of that direction.

Joe Henry has been exploring the relationship between songs and their aural atmosphere for a quarter of a century. His early albums cloaked his carefully crafted compositions in a variety of artful atmospheres provided by other producers, like T-Bone Burnett and Anton Fier, but he began to hit his stride in the early ˜90s, when he took the production reigns himself on a pair of albums”Short Man’s Room and Kindness of the World”that found him backed by alt-country heroes The Jayhawks. With 1996’s Fuse, Henry began pursuing an increasingly unconventional production muse, employing everything from ambient synthesizer textures to the saxophone of Ornette Coleman (the jazz giant plays on 2001’s Richard Pryor Addresses a Tearful Nation). With each album from Fuse up through 2009’s Blood From Stars, Henry’s production became increasingly more impressionistic, but his latest, Reverie, marks a reversal of that direction.

It should be noted, of course, that Henry has also spent the last several years as a producer for others, helming projects for a wide spectrum of artists that runs from the late, great soul man Solomon Burke to New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint. During that time, he’s had the opportunity to investigate all manner of American roots styles, which may have affected his decision to make Reverie an organic, all-acoustic, live-in-the-studio affair. Certainly Henry’s work on The River In Reverse, the collaboration Toussaint cut in the Crescent City in 2005 with Elvis Costello, had an effect on him. We worked really, really hard on that record, Henry recalls, it was an incredibly intense, brief period of time. We all felt honored to be there, especially given what had just happened in New Orleans. We were all freshly awakened to how important the music of that city has been. And here’s Allen, the living patriarch of that music”to be in service to him in that moment felt like a tremendous gift.

It should be noted, of course, that Henry has also spent the last several years as a producer for others, helming projects for a wide spectrum of artists that runs from the late, great soul man Solomon Burke to New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint. During that time, he’s had the opportunity to investigate all manner of American roots styles, which may have affected his decision to make Reverie an organic, all-acoustic, live-in-the-studio affair. Certainly Henry’s work on The River In Reverse, the collaboration Toussaint cut in the Crescent City in 2005 with Elvis Costello, had an effect on him. We worked really, really hard on that record, Henry recalls, it was an incredibly intense, brief period of time. We all felt honored to be there, especially given what had just happened in New Orleans. We were all freshly awakened to how important the music of that city has been. And here’s Allen, the living patriarch of that music”to be in service to him in that moment felt like a tremendous gift.

In fact, Henry views his production work as sort of an extension of his solo career. I still look at everything from the point of view of a songwriter and a recording artist, he says. In both cases I just want something living to come out of the speakers that means something to us. The fact that I’m producing a lot of records for other people keeps me feeling like I’m working all the time, I can learn something working for somebody else and bring it back to my own projects when they happen. I’m not an engineer, I don’t know how to run ProTools. What I do offer is the point of view of somebody who has taught myself since I was in my mid teens how to make a song feel illuminated.

Like Randy Newman, Henry is a writer whose repertoire depends greatly on inhabiting characters far removed from his true personality. His songs stand or fall on his ability to convince you that he’s somebody else. I’m not somebody who ever developed a persona that walks out in front of me, he explains. I just wanted to write the kind of songs that I could disappear into. I don’t have a persona to sell. People said that to me in fairly brutal terms, at one point, that the reason I had never ˜broken through’ as an artist was because I don’t have a recognizable, identifiable persona that’s marketable. I made a decision to want to write songs that could engulf me. I think the song has to have the persona. If the song has enough character, then I can be that character in the context of recording or performing it. That’s plenty of character.

While the intensely poetic nature of Henry’s lyrics doesn’t always make it easy to tell the identity of the narrator, it’s obvious that he’s moving through some widely varied scenarios over the course of Reverie. It turns out that a dramatic arc was a large part of what he had in mind from the outset. I’m somebody who’s been devoted to listening to albums as a complete form, says Henry. Like a movie, like a three-act play, it’s a form that we understand. I would hope that people would listen to Reverie as a full piece at some point, because it was constructed to play like a movie, in a particular sequence. I’ve put enough thought into it that that level of listening is gratified.

On the sonic side of things, Henry has applied perhaps the most naturalist production techniques of his career to Reverie. Most of the album is just Henry on acoustic guitar backed by piano, standup bass and drums, recorded with as much room sound as possible. The idea for this approach came to him in an unlikely context. I was wandering alone around the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, he explains. I was looking at some really, really early Picasso drawings and paintings, probably from his teens. They were small pieces of wood and pieces of cardboard. Looking at these pictures, I heard what Reverie sounded like. [I thought] ˜I want to do in songs what he’s doing there.’ I just knew instantly what this thing needed to sound like. In the next twenty minutes walking through the museum I knew who would be in the room [for the recording], I knew how we would set up, I knew that I would leave the windows open to the microphones so that everything that happens around the songs was available. I knew if we were set up in the room as close to each other as we could be”I didn’t know what that would sound like, but I knew what it would sound like would be the right thing.

On the sonic side of things, Henry has applied perhaps the most naturalist production techniques of his career to Reverie. Most of the album is just Henry on acoustic guitar backed by piano, standup bass and drums, recorded with as much room sound as possible. The idea for this approach came to him in an unlikely context. I was wandering alone around the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, he explains. I was looking at some really, really early Picasso drawings and paintings, probably from his teens. They were small pieces of wood and pieces of cardboard. Looking at these pictures, I heard what Reverie sounded like. [I thought] ˜I want to do in songs what he’s doing there.’ I just knew instantly what this thing needed to sound like. In the next twenty minutes walking through the museum I knew who would be in the room [for the recording], I knew how we would set up, I knew that I would leave the windows open to the microphones so that everything that happens around the songs was available. I knew if we were set up in the room as close to each other as we could be”I didn’t know what that would sound like, but I knew what it would sound like would be the right thing.

This kind of ad hoc, no-prisoners method of record-making is a far cry from the elaborate soundscapes of some of Henry’s other releases, but that’s exactly what he likes about it. This is an album that spontaneously squeaks, rattles, and rumbles in all the right places. I deliberately constructed Reverie to be unmannered, he says. It’s quite different in a way from the last record, Blood From Stars, which I envisioned to be more of a widescreen affair. I think Reverie feels more like live theater versus the widescreen movie. I wanted Reverie to feel like something I just pulled out of the earth.