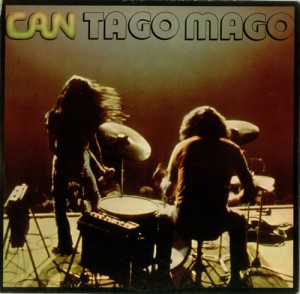

Riffs, Rants & Rumors: Can's Crowning Krautrock Moment

posted in: Features • Rock

Nothing is true, everything is permitted. So goes the famous maxim popularized by Vladimir Bartol‘s 1938 novel, Alamut, and attributed to eleventh century Persian revolutionary Hassan-i Sabbah. If there’s any album falling even nominally under the “rock” umbrella that embodies that aphorism, it’s Can‘s 1972 masterpiece, Tago Mago. In the context of twentieth century music, the pioneering German band was as revolutionary as Sabbah. Even within the wide-open world of late-’60s/early-’70s Germany’s krautrock scene”where psychedelia, free jazz and avant-garde electronic techniques were mixed into a musical Molotov cocktail that exploded old ideas about what rock music could contain”Can was working without a net, and Tago Mago was their ultimate high-wire act.

Nothing is true, everything is permitted. So goes the famous maxim popularized by Vladimir Bartol‘s 1938 novel, Alamut, and attributed to eleventh century Persian revolutionary Hassan-i Sabbah. If there’s any album falling even nominally under the “rock” umbrella that embodies that aphorism, it’s Can‘s 1972 masterpiece, Tago Mago. In the context of twentieth century music, the pioneering German band was as revolutionary as Sabbah. Even within the wide-open world of late-’60s/early-’70s Germany’s krautrock scene”where psychedelia, free jazz and avant-garde electronic techniques were mixed into a musical Molotov cocktail that exploded old ideas about what rock music could contain”Can was working without a net, and Tago Mago was their ultimate high-wire act.

Can had already released two albums before Tago Mago, each one overflowing with new ideas about organizing sound in a song-like format. But on their third record”out now in a deluxe, two-CD fortieth anniversary reissue”they pretty much tossed their tiny handful of concessions to convention into the fire, and made music ideal for dancing in front of the flames. Perhaps not coincidentally, Tago Mago was Can’s first proper album project with singer Damo Suzuki, a Japanese street singer who first crossed the band’s path in 1970. Original Can vocalist Malcolm Mooney began going off the psychological rails shortly after the recording of the group’s 1969 debut album, Monster Movie. Can’s follow-up, Soundtracks, gathered together cuts they recorded for a number of underground films, and it featured both Mooney and Suzuki.

In the esteemed company of keyboard wizard Irmin Schmidt, young guitar antihero Michael Karoli, poet of percussion Jaki Liebezeit and Can’s resident visionary, bassist/tape-manipulator Holger Czukay”a fiercely eclectic, expressive and inventive bunch to begin with”Suzuki was both the wild card and the joker in the deck. He’s said to have improvised all his lyrics for the tunes on Tago Mago, never even committing them to paper, and floating freely between English, Japanese, and sometimes, some dialect seemingly of his own invention. Like his Can comrades, he challenged the traditional notion of his role in a rock band. The notion of singing in the classical sense doesn’t quite capture the range of sounds Suzuki creates over the course of the album”from his James Brown-in-outer-space ululations on the space-age funk of Mushroom to his straitjacket-bait shrieking on Peking O (and they say Mooney was the one with a precarious mental condition), Suzuki redefines the very process of standing in front of a microphone during a recording session.

In the esteemed company of keyboard wizard Irmin Schmidt, young guitar antihero Michael Karoli, poet of percussion Jaki Liebezeit and Can’s resident visionary, bassist/tape-manipulator Holger Czukay”a fiercely eclectic, expressive and inventive bunch to begin with”Suzuki was both the wild card and the joker in the deck. He’s said to have improvised all his lyrics for the tunes on Tago Mago, never even committing them to paper, and floating freely between English, Japanese, and sometimes, some dialect seemingly of his own invention. Like his Can comrades, he challenged the traditional notion of his role in a rock band. The notion of singing in the classical sense doesn’t quite capture the range of sounds Suzuki creates over the course of the album”from his James Brown-in-outer-space ululations on the space-age funk of Mushroom to his straitjacket-bait shrieking on Peking O (and they say Mooney was the one with a precarious mental condition), Suzuki redefines the very process of standing in front of a microphone during a recording session.

Speaking of which, like everything else about Tago Mago, even the album’s birthplace was unconventional. The record was made in a centuries-old German castle called Schloss Ní¶rvenich, owned at the time by a Can-friendly patron of the arts. From within those castle walls, Can forged a sound that was as full of shadowy mystery as fiery invention; a key influence on the band at the time was the infamous early-twentieth century British occultist Aleister Crowley, who also figures into the legends of first-gen UK hard-rock heroes like Ozzy Osbourne and Jimmy Page. But dark and light become relative concepts in the constantly shifting, multi-colored maze of tones and textures that make up the seven tracks on the original double-LP of Tago Mago, most of which extended well beyond the common runtime for a song even in those heady hippie days. The eighteen-and-a-half-minute Halleluwah, for instance”a classic of the krautrock canon”sounds like acid rock in the truest sense of the term, music meant to evoke an LSD trip, not merely to accompany one. And the squeaks, squawks and scrapings that run ominously through the electro-acoustic 17:37 tone poem Aumgn”alongside everything from a barking dog to a tumbling avalanche of tom toms”are like being inside an active volcano before, during and immediately after its eruption.

But the 2011 reissue of Tago Mago extends the grand aural hallucinations even futher by adding a second disc of previously unreleased live material. Live 1972 takes of Halleluwah, Mushroom and Spoon prove definitively that what the band achieved in the cloistered confines of Schloss Ní¶rvenich wasn’t just a fluke. If anything, Can leans into the songs with even more freaky fervor than on the studio versions. Listening to Michael Karoli go wild with a post-Hendrix blend of sorcery and savagery on Spoon, or hearing Irmin Schmidt’s anxiety-attack organ riffs on Halleluwah, one can’t help but wonder whether it was Malcolm Mooney’s brief membership in the band that contributed to his psychological travails.

But the 2011 reissue of Tago Mago extends the grand aural hallucinations even futher by adding a second disc of previously unreleased live material. Live 1972 takes of Halleluwah, Mushroom and Spoon prove definitively that what the band achieved in the cloistered confines of Schloss Ní¶rvenich wasn’t just a fluke. If anything, Can leans into the songs with even more freaky fervor than on the studio versions. Listening to Michael Karoli go wild with a post-Hendrix blend of sorcery and savagery on Spoon, or hearing Irmin Schmidt’s anxiety-attack organ riffs on Halleluwah, one can’t help but wonder whether it was Malcolm Mooney’s brief membership in the band that contributed to his psychological travails.

In the four decades since Tago Mago was recorded, it has cast a long shadow over the more adventurous end of the rock spectrum”everyone from John Lydon to Radiohead has been inspired by its uncompromising originality. Its influence has also seeped into other media”the soundtrack to last year’s film adaptation of the Haruki Murakami novel Norwegian Wood included Tago Mago‘s Bring Me Coffee Or Tea. And it seems entirely plausible that with the extension of the album’s legacy via its expanded reissue, Tago Mago could infect the emerging aesthetics of a whole new generation of sonic adventurers.