Riffs, Rants and Rumors: Can Rewrites Krautrock History

posted in: Exclusive Interviews • Features • Rock

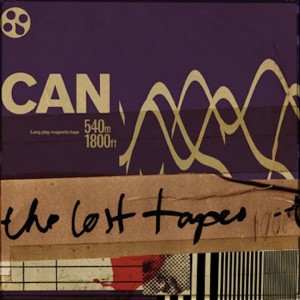

It’s hard to tell now whether the term “krautrock””originally concocted by the British music weeklies as a catch-all for the experimentally-minded bands coming out of Germany in the beards-and-bellbottoms era ”was intended derisively or not, regardless of it’s political incorrectness. But after German band Faust used the appellation for a song title in 1973, it started to transcend its origins, and over the decades it has become a generic tag for the post-psychedelic sonic storms stirred up by the likes of Amon Duul II, Guru Guru, Faust, Ash Ra Tempel and Can, as well as their more electronically minded cousins, Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, et al”music that has been incalculably influential to every generation of rockers to come along since. But while classic albums by the aforementioned artists have been comfortably ensconced in the krautrock canon for some forty years now, the books may have to be reopened in order to accomodate the arrival of The Lost Tapes, three CDs’ worth of recently unearthed, previously unheard, archival Can material that seems sure to blow more than a few fans’ minds.

It’s hard to tell now whether the term “krautrock””originally concocted by the British music weeklies as a catch-all for the experimentally-minded bands coming out of Germany in the beards-and-bellbottoms era ”was intended derisively or not, regardless of it’s political incorrectness. But after German band Faust used the appellation for a song title in 1973, it started to transcend its origins, and over the decades it has become a generic tag for the post-psychedelic sonic storms stirred up by the likes of Amon Duul II, Guru Guru, Faust, Ash Ra Tempel and Can, as well as their more electronically minded cousins, Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, et al”music that has been incalculably influential to every generation of rockers to come along since. But while classic albums by the aforementioned artists have been comfortably ensconced in the krautrock canon for some forty years now, the books may have to be reopened in order to accomodate the arrival of The Lost Tapes, three CDs’ worth of recently unearthed, previously unheard, archival Can material that seems sure to blow more than a few fans’ minds.

Can’s most fertile period, from 1969 to 1974, is the focus of The Lost Tapes. During that time, the band mixed the adventurous spirit of the times with a little bit of everything. Can keyboardist Irmin Schmidt explains the genesis of the band’s genre-jumping sound, recalling, “In ’66 I was a classical composer¦I learned to compose [by studying] with Ligeti and Stockhausen, and also I was a conductor and a pianist. At the same time I was quite fascinated by a lot of contemporary jazz and [was intrigued] when Frank Zappa & the Mothers came out, and Jimi Hendrix appeared. Then in ’66 I was sent to New York for the Metropolis conductors’ contest…I met people like [New York avant-gardists] La Monte Young and Steve Reich and Terry Riley¦and I came back with big doubts about what I was doing as a classical musician.” Schmidt determined it was time to bring together rock, jazz and avant-garde classical concepts in a band format. “I started working on that and founded a group of musicians,” he explains, “with a real jazz drummer [Jaki Liebezeit], another classically educated musician [bassist Holger Czukay], and a young rock guitarist [Michael Karoli], and we didn’t have any precise idea where that should develop into what, so it seemed to be logical it became Can.”

On albums like Monster Movie and Tago Mago, Can also incorporated R&B-inspired grooves and world music influences, creating a heady swirl of sounds that could shift easily from frenzied to meditative, with help from the band’s vocalists, American singer Malcolm Mooney and his Japanese successor, Damo Suzuki. Early in the band’s career, their musical mad-scientist laboratory was actually located inside an old German castle. “It was owned by an art collector who was a friend of mine,” Schmidt recalls, “I was very much into the art scene, writing about painting and holding speeches in galleries for openings. He owned a castle and he gave us a room to work in, and that was the first studio. But then we had to move out, because we used the hallway for reverb…somebody was living with his family upstairs. We were torturing him, he couldn’t sleep because we were making so much noise. So we moved out of there, and moved into the final Can studio which we kept for the rest of Can’s tenure.”

On albums like Monster Movie and Tago Mago, Can also incorporated R&B-inspired grooves and world music influences, creating a heady swirl of sounds that could shift easily from frenzied to meditative, with help from the band’s vocalists, American singer Malcolm Mooney and his Japanese successor, Damo Suzuki. Early in the band’s career, their musical mad-scientist laboratory was actually located inside an old German castle. “It was owned by an art collector who was a friend of mine,” Schmidt recalls, “I was very much into the art scene, writing about painting and holding speeches in galleries for openings. He owned a castle and he gave us a room to work in, and that was the first studio. But then we had to move out, because we used the hallway for reverb…somebody was living with his family upstairs. We were torturing him, he couldn’t sleep because we were making so much noise. So we moved out of there, and moved into the final Can studio which we kept for the rest of Can’s tenure.”

It was at Can’s Inner Space Studio, outside Cologne, that The Lost Tapes were retrieved. In fact, the three hours of music the set contains were painstakingly culled by Schmidt and his accomplice Jono Podmore from about ten times as much material. Much of it comes from soundtrack recordings the group worked on for European films. “It was forgotten that there was good music on the film scores,” says Schmidt, “but it was in pieces, these film music suites on Lost Tapes we put together like we would have done in the ˜70s, made a montage, that’s what Jono did…in the way we [Can] have always put bits and pieces together; we did that very often.”

Can fans may also be able to identify elements of well-known tracks by the band in the work tapes unearthed for this collection. “Sometimes there are pieces on The Lost Tapes where it’s a work in progress towards a piece that was actually put onto an album,” reveals Podmore, “We’ve got an earlier state of a piece that ended up on an album, but they’re interesting in their own right, especially when you’re using contemporary editing techniques.”

Schmidt adds, “Those tapes too show something about the process of how Can music was created. Like I even gave a hint in the title for instance, ‘On the Way to Mother Sky.’ It’s really an earlier state of when we worked on the piece ‘Mother Sky’ from [1970 Can album] Soundtracks. And the same thing on different themes of ‘Vitamin C’ [from 1972’s Ege Bamyasi]. I find this process very interesting to show, which is one exciting thing about The Lost Tapes.”

Much of what one hears on The Lost Tapes, not to mention the classic Can albums, had its beginnings in collective improvisation, but Schmidt is quick to point out that it wasn’t merely stoned jamming. “We were improvising, but improvising always with a very considered idea behind it,” he says, “starting maybe chaotic but immediately focusing on something which appeared to be strong, like a strong groove, and concentrating on that. So it was not just fooling around for two hours, it was as much as possible concentrating on the real spontaneous composition of the concept of a piece.”

From the ferocious, minimalist-rock stomp of “Waiting for the Streetcar,” replete with Mooney’s maniacal, obsessive-sounding repetitions of the title phrase, to some of the more subtly nuanced, soundtrack-derived pieces, The Lost Tapes offers up a comprehensive view of Can’s multiple musical personalities even as it illuminates formerly unknown corners of the Can universe. Looking back on the music he made so many years earlier, Schmidt is enthusiastic, but vehemently abjurant of nostalgia. “I was glad to find good pieces,” he allows, “with some of them I was really surprised, of course. I was surprised to find pieces Malcolm was singing on which we never gave a chance to be released, so I was quite happy. I have a very unsentimental approach towards this, there’s no nostalgic emotions. I listen to it like it’s from somebody else, especially if you find something good. It has lost the blood on it, it’s like from somebody else. And the more it’s from somebody else, the better.”